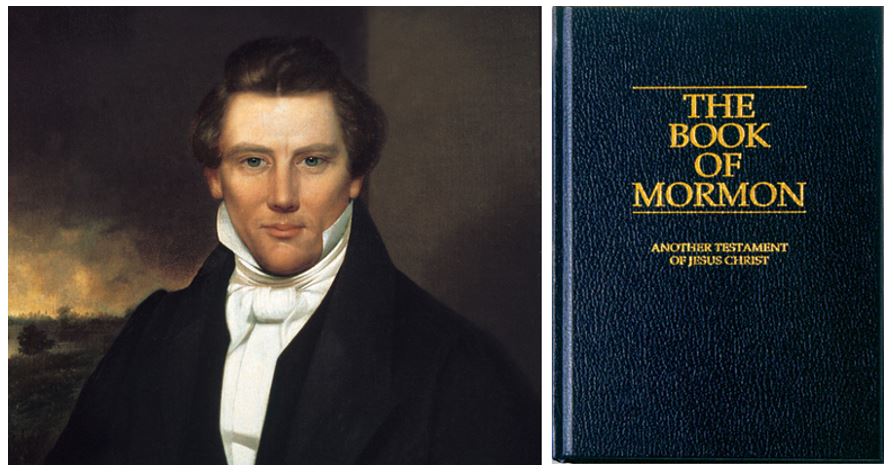

Book of Mormon Modern Expansion Theory

It’s time to shatter past, false assumptions and expectations of the Book of Mormon.

M. Russell Ballard in Feb 2015 to CES employees:

Let me warn you not to pass along faith promoting or unsubstantiated rumors or outdated understandings and explanations of our doctrines or practices from the past…Consult the works of recognized, thoughtful and faithful LDS scholars to ensure you do not teach things that are untrue, out of date, or odd and quirky.

We have been teaching the Book of Mormon and scripture in general in a way that perpetuates outdated understandings and false explanations of its origins and intent. This sets up members of the church with too lofty of a view that is susceptible to faith crisis when they encounter the critical information floating around. In this article, I will collate the logic of over a dozen faithful LDS scholars to introduce a new perspective of LDS scripture, especially the Book of Mormon.

In my last blog, I talked about how the Book of Mormon contains “too 19th century sounding” content, especially related to a mature dialogue of Christian doctrines and ideas. This blog will explore whether this is proof that it the BOM is “false” or if there are other, acceptable explanations of why legitimate scripture could be formed this way.

LDS Understanding of the Bible

A large part of the problem with our view of the Book of Mormon is in our understanding of the Bible and expectation for scripture in general.

Many LDS have a very literal, fundamentalist view of the Bible. We assume Moses wrote the Pentateuch. We assume Isaiah wrote Isaiah. We assume eyewitnesses Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John wrote the gospels named after them. We assume that the writings we have in the Bible were written by prophets and apostles of God, who held the priesthood and authority of God.

We now understand the Pentateuch was a composite work that came together from a combination of various literary pieces and oral traditions, written hundreds of years after Moses and being reworked and revised until the final state we have. The Book of Isaiah includes chapters that weren’t written until 100 years after Isaiah’s death. The New Testament gospel books contain stories directly attributable to Jesus Christ but also mix in significant expansions and commentaries by unknown authors decades after the death of the apostles. Techniques utilizing concepts of midrash and pseudepigrapha are common.

Midrash is a technique where a prior work is appropriated, embellished, reworked, or adapted to fit a new context. The Book of Chronicles and many passages of the New Testament fall into this category. (author note after receiving some well deserved criticism on my use of the term midrash: midrash is a misunderstood and controversial subject. Midrash in the purest sense, refers to a body of work by Jewish Rabbi’s, which are collected and accepted as quasi-official scripture commentary within Judaism, ranging from 100 BC to about 1,000 AD. In a broader sense, the term is commonly used–perhaps mistakenly–to refer to the literary technique the Rabbi’s used to take scripture and expound on it doctrinally and historically, as if missing elements are being restored.)

Pseudepigrapha is a genre of sacred writing where the author would falsely attribute the book to a well known historical figure.

Christian and Jewish scholars have made many advancements over the past 200 years in understanding how the Bible was formed to identify what is actual history, who were the actual authors, etc. German Christian scholars came up with the term heilsgeschichte that is useful for this discussion.

German has two words that are translated into the word “history” in English: geschichte and historie. Historie has to do with facts and dates and things that can actually be proven. Geschichte has to do with reports, stories, and tales that relate to history. German scholars created the word heilsgeschichte, combining the word heils (holy) with geschichte translated into English as “Salvation History” or “Story of Salvation”.

Robin Routledge in Old Testament Theology: A Thematic Approach, said:

The stories recorded by the OT writers are not inventions: they are founded on actual events. However, what appears in the OT is the end result of constant telling and retelling, and corresponds not to actual history, but heilsgeschichte: the story of salvation as viewed through the eyes of Israel’s faith, and in which the significance of divine action is brought home to each new generation of believers.

Fundamentalist Evangelical Christians might believe the Bible is 100% historie, and some LDS share that view (a recent Pew Research study showed 57% of Evangelicals and 52% of LDS believe in the Adam and Eve Creation account literally), but most LDS don’t feel the need for that constraint. Many LDS are fine viewing stories like Noah’s flood, the Tower of Babel, and the Garden of Eden Adam and Eve creation account as figurative and not actual history. We’re usually OK with a Gospel Doctrine teacher bringing in authorship theories on the Epistle to the Hebrews, for example. If you notice closely, you see Elder Holland referring to the “author of Hebrews” not “Paul” when he quotes from that book.

But, though it’s acceptable to reject a Fundamentalist view of the Bible, it’s not as acceptable to reject a Fundamentalist view of the Book of Mormon or other LDS scripture this way. Perhaps this is due to the Article of Faith.

8 We believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly; we also believe the Book of Mormon to be the word of God.

The difference seems to be that we believe the Book of Mormon was translated correctly, but we’re not so sure about the Bible. Which leads us to a discussion of what Joseph Smith meant when he used the word “translate”.

Translation

The final words of the Book of Mormon Title Page declares the Book of Mormon to be:

TRANSLATED BY JOSEPH SMITH, Jun.

The word translate usually typifies a secular process where one who knows two languages studies and compares in order to convert the original language text into the new language text. Since Joseph didn’t know the languages he was translating, this is clearly not what Joseph meant. Using evidence of how Joseph used this word, we must deduce what he meant by “translate”. Let’s look at a few examples of how Joseph used the word translation.

JST of the Bible

Joseph suspected there were errors in the Bible was translated, so he embarked on the “Joseph Smith Translation” of the Bible.

LDS scholar Stephen Robinson said:

Or course we believe the JST is ‘inspired.’ but that is not the same thing as saying it always restores the original texts of the bible books. In 1828 the word translation was broader in its meaning than it is now, and the Joseph Smith translation (JST) should be understood to contain additional revelation, alternate readings, prophetic commentary or midrash, harmonization, clarification and corrections of the original as well as corrections to the original.

The Joseph Smith Translation (JST) is not a translation in the traditional sense. Joseph did not consider himself a ‘translator’ in the academic sense. The JST is better thought of as a kind of ‘inspired commentary’–Joseph was not usually restoring ‘lost text’ (though in some few cases he may have). The Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible is not, as some members have presumed, simply a restoration of lost Biblical text or an improvement on the translation of known text. Rather, the JST also involves harmonization of doctrinal concepts, commentary and elaboration on the Biblical text, and explanations to clarify points of importance to the modern reader.

Robert J. Mathews, the former Dean of Religion at BYU and conservative LDS scholar said this about the JST.

Joseph himself called his work a ‘translation.’ This is apparently the sense in which he understood the work he was doing with the Bible. Since in part he was effecting a restoration of lost meaning and material, and since the Bible did not originate in English, his work to some degree would amount to an inspired, or revelatory, ‘translation’ into English of that which the ancient prophets and apostles had written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and/or Greek.

Joseph Smith neither had nor claimed a knowledge of the Greek or Hebrew languages, nor did he work from manuscripts written in these languages. He was not a novice at translation, however, for just previously, with divine assistance, he had translated the Book of Mormon from metal plates upon which was engraved what is known as the ‘reformed Egyptian’ language.

The Prophet Joseph claimed a divine appointment to translate the Bible [D&C 45:60-61; 76:15], and he also claimed divine revelation in the translation process [D&C 76:15-18 …].

It is not a translation in the usual sense, although the Prophet Joseph Smith consistently referred to it as a translation. In the Doctrine and Covenants, too, it is referred to as a translation.

From this, we get a good understanding of what Joseph meant by the word translation. It seems he references it broadly to apply to anything a prophet does to produce inspired work that is directly or indirectly related to an earlier text.

Book of Abraham

The Book of Abraham, like the Book of Mormon, starts with the declaration:

Translated from the Papyrus, by Joseph Smith

In the essay the church published on Book of Abraham translation, the church officially authorizes the use of the “catalyst theory”. This is a theory that has been circulating among LDS apologists for many years since the original papyri were found and translated and found that they do not contain the ancient writings of Abraham. The catalyst theory is that though the Book of Abraham was not written on the papyri, Joseph used the papyri as a catalyst to channel the revelatory spirit and was able to produce inspired scripture.

Alternatively, Joseph’s study of the papyri may have led to a revelation about key events and teachings in the life of Abraham, much as he had earlier received a revelation about the life of Moses while studying the Bible. This view assumes a broader definition of the words translator and translation. According to this view, Joseph’s translation was not a literal rendering of the papyri as a conventional translation would be. Rather, the physical artifacts provided an occasion for meditation, reflection, and revelation. They catalyzed a process whereby God gave to Joseph Smith a revelation about the life of Abraham, even if that revelation did not directly correlate to the characters on the papyri.

…By analogy, the Bible seems to have been a frequent catalyst for Joseph Smith’s revelations about God’s dealings with His ancient covenant people. Joseph’s study of the book of Genesis, for example, prompted revelations about the lives and teachings of Adam, Eve, Moses, and Enoch, found today in the book of Moses.

Book of Mormon

It was assumed for a long time that the Book of Mormon was a very “tight” translation. Recently, many LDS scholars are suggesting it was a very “loose” translation. Or at a minimum, some combination of the two. Tight would mean that it was a God breathed translation word for word converting an ancient text to modern English. Loose would mean Joseph was free to choose words and phrases or even to significantly expand the text beyond its original state.

David Whitmer said the following.

Joseph Smith would put the seer stone into a hat, and put his face in the hat, drawing it closely around his face to exclude the light; and in the darkness the spiritual light would shine. A piece of something resembling parchment would appear, and under it was the interpretation in English. Brother Joseph would read off the English to Oliver Cowdery, who was his principal scribe, and when it was written down and repeated to brother Joseph to see if it was correct, then it would disappear, and another character with the interpretation would appear.

This is a late quote, but we see quotes like this from Emma Smith, Martin Harris, and Oliver Cowdery enough that we believe this was a valid description of the dictation process.

Joseph never specifically clarified how the Book of Mormon translation process went. He never added to the simple declaration of the Book Mormon’s title page that it was by the “gift and power of God.” We can trust that we understand a bit about the dictation process, ie how it went from Joseph’s mind to the scribes. But we still don’t understand the translation process, which is how it got into Joseph’s mind.

I believe the accounts like David Whitmer’s on how the Book of Mormon was dictated have led us to ignore other clear evidence that suggests the translation process was a very “loose” process.

The best insight we get into the Book of Mormon translation process is probably from the Book of Commandments Chapters 7-8, preserved with minor alterations in the Doctrine and Covenants.

1. Oliver Cowdery was commanded to translate a portion of the Book of Mormon. Book of Commandments 7:4

…Ask that you may know the mysteries of God, and that you may translate all those ancient records, which have been hid up, which are sacred, and according to your faith shall it be done unto you.

2. It appears Oliver was successful at first but then ultimately failed. Book of Commandments 8:2

… behold it is because that you did not continue as you commenced, when you begun to translate, that I have taken away this privilege from you.

3. The reasons Oliver failed, with fascinating insight into how the translation process worked. Book of Commandments 8:3

3 Behold you have not understood, you have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought, save it was to ask me; but behold I say unto you, that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it is right, I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you: therefore, you shall feel that it is right; but if it be not right, you shall have no such feelings

It appears the translation process was a collaborative process where the translator would “study it out” in his mind. With no ability to read the language of the original text, this is clearly a creative process. Then God confirms whether the creative attempt was right or wrong. Oliver’s mistake was not that he was “guessing” wrong, it was that he sat with an empty mind expecting God to give him the translation.

Additionally, what is meant by right in “if it be right”? We see from the KJT translation process, that clearly right doesn’t always mean “equating to the original text”, but right may include any text which “harmonizes with other scripture” or otherwise brings forth God’s inspired word.

In the church’s essay on Book of Abraham, the translation process of the Book of Abraham and Book of Mormon are compared several times. Both were inspired by a physical document. In both cases, Joseph did not know the language of the original document. In both cases, it appears the original document was not necessary to the process other than possibly as a catalyst.

The church’s essay confirms the Oliver Cowdery episode as the best insight into Joseph’s translation process:

Neither the Lord nor Joseph Smith explained the process of translation of the book of Abraham, but some insight can be gained from the Lord’s instructions to Joseph regarding translation. In April 1829, Joseph received a revelation for Oliver Cowdery that taught that both intellectual work and revelation were essential to translating sacred records. It was necessary to “study it out in your mind” and then seek spiritual confirmation.

Reworking and Editing of Translated Scripture

More insight into the prophet’s understanding of the concept of ‘translation’ comes from how he dealt with the Book of Mormon text after it was translated. After the initial publication of the Book of Mormon in 1830, Joseph Smith continued to revise the book and fix errors with updates in 1837 and 1840. Over 2,000 corrections were made, mostly grammar and spelling. Some of those were actually fixing mistakes that were correct in the original manuscript but changed in the printed edition.

But many of the changes were doctrine related, especially changing references of Jesus Christ as ‘God’ to ‘Son of God’ or ‘Eternal Father’ to ‘Son of the Eternal Father’. Another was to change the converted Lamanites from ‘white and delightsome’ to ‘pure and delightsome’. A similar process took place for the Book of Commandments. Joseph continued to rework revelations, even after they were published. Joseph saw the canon as open. He saw himself as authorized to make changes freely as he saw fit. As his understanding improved, he felt authorized to update the Book of Mormon and Book of Commandments. He clearly saw revelation and translation as fluid, dynamic concepts.

Now, let’s get practical and look at two theories that LDS could adopt that incorporate these ideas.

Expansion Theory

Blake Ostler first introduced his Expansion Theory in 1987 article in Dialogue, “The Book of Mormon as a Modern Expansion of an Ancient Source”. Ostler views the Book of Mormon as a combination of an ancient text and Joseph’s expansion, resulting in a “modern world view and theological understanding”.

A good example of this is King Benjamin’s address found in Mosiah 2-5. Ostler sees modern elements of Joseph’s environment, such as 19th century revival meeting similarities, camping in tents for several days, call to repent and accept Christ, attenders would experience change of heart, etc. But he also sees distinctly ancient elements: call for entire nation to gather to witness coronation of king, burnt offerings, covenant renewal, etc. He believes traditional LDS apologists are unable to sufficiently explain the modern elements, but critics are unable to explain for the complexity and ancient elements in ways that are “above Joseph”. The only sufficient explanation is to combine the two, using his Expansion Theory.

According to Ostler, similar to the way the Bible came together, with authors incorporating elements of pseudepigrapha, midrash, and exegis, the Book of Mormon seamlessly combines the ancient text with Joseph’s expansion without defining when the breaks come. Critics cry ‘why didn’t he tell us he did this? He claimed it’s all from ancient prophets!’ Ostler would answer that Joseph, seeing himself as a prophet with authority from God to do so, brought forth scripture, in the exact same way it was done anciently, which is to embed the modern with the old together, and not explicitly define the difference.

The expansion theory has become more popular as more faithful scholars and lay readers recognize the modern elements of the Book of Mormon.

LDS scholar Jan J. Martin, makes a convincing and interesting case that the Book of Mormon was aware of 16th century debates between William Tyndale and Thomas More when it comes to the English translation of passages in the Bible.

In an interview with Bill Reel, faithful LDS scholar Richard Bushman was asked about whether it was OK to view the Book of Mormon as non-historical, he answered:

Richard Bushman: Some years ago if someone told me the Book of Mormon wasn’t historically accurate, that it was some kind of modern creation, I would have thought they were heretical. I wouldn’t say that anymore. I think there are faithful Mormons who are unwilling to take a stand on the historicity. I disagree with them, I think it is a historical book, but I recognize that a person can be committed to the gospel in every way and still have questions about the Book of Mormon.

Bill Reel: You would make room for people in the church who don’t believe the Book of Mormon is a historical text but somehow Joseph is giving us scripture from a modern perspective?

Richard Bushman: Yes I would. I know people of that kind. And they are very good people.

LDS scholar Grant Hardy seems to agree with much of Ostler’s approach. Rather than try to justify the Deutero Isaiah problems of Second Nephi with twisted explanations attempting to preserve the traditional view (that Nephi got Deutero Isaish either from the Brass Plates or an angel), Hardy says:

A more promising avenue for the faithful, it seems, is to acknowledge that we probably know less about what constitutes an ‘inspired translation’ than we do about ancient Israel.

He then goes into an explanation about midrash, showing how the Book of Mormon could be using a similar technique. Hardy also used an interesting example to explain how he views BOM historicity. He used the example of the Broadway musical 1776. The play is a modern, artistic adaption of a prior literary work, which was a non-historian’s view of a historical event. Comparing this kind of view to the Book of Mormon, we should not be surprised to see anachronisms in such a work like Joseph’s expansions on Christian principles or historical issues like horses and chariots in America or the back story of the Jaredites including the Noah’s flood and Tower of Babel myths, but we still understand there to be an actual history behind it.

The expansion theory has a degree of validation in an academic setting from a non-Mormon scholar. James Charlesworth on Mosiah 3:8-10 acknowledged:

In these three verses, we find what most critical scholars would call clearly Christian phrases; that is, the description is so precise that it is evident it was added after the event. The technical term for this phenomenon is vaticinium ex eventu. The specific details are the clarification that the Messiah will be called ‘Jesus Christ,’ that his mother will be called Mary, that salvation is through faith—indeed faith on his name—that many will say he has a devil, that he will be scourged and crucified, and finally that he will rise on the third day from the dead. Do not these three verses contain a Christian recital of Christ’s life?

How are we to evaluate this new observation? Does it not vitiate the claim that this section of the Book of Mormon, Mosiah, was written before 91 B.C.? Not necessarily so, since Mormons acknowledge that the Book of Mormon could have been edited and expanded on at least two occasions that postdate the life of Jesus of Nazareth. It is claimed that the prophet Mormon abridged some parts of the Book of Mormon in the fourth century A.D. And likewise it is evident that Joseph Smith in the nineteenth century had the opportunity to redact the traditions that he claimed to have received.

Today biblical scholars are making significant and exciting discoveries into the various strata of ancient documents through the use of what is called Redaction Criticism, a method employed to discern the editorial tendencies of an author-compiler. Perhaps it would be wise for specialists to look carefully at this phenomenon in the Book of Mormon. The recognition that the Book of Mormon has been edited on more than one occasion would certainly explain why certain of the messianic passages appear to be Christian compositions.

Blake Ostler on whether the expansion theory undermines BOM historicity:

Some may see the expansion theory as compromising the historicity of the Book of Mormon. To a certain extent it does. The book cannot properly be used to prove the presence of this or that doctrine in ancient thought because the revelation inherently involved modern interpretation. When we find aspects of the book that show evidences of an ancient setting or thought that is best interpreted from within an ancient paradigm, we should acknowledge the possibility that an ancient text underlies the revelation. Such a model does not necessarily abrogate either the book’s religious significance or its value as salvation history. After all, much of the Bible is a result of a similar process of redaction, interpolation, and interpretation.

The LDS scholars that support this theory generally seem to agree on a couple traditional points.

- Though there is modern expansion, there is some underlying ancient text

- Gold plates are real

So this theory can go a long ways to explain some of the traditional criticism of the Book of Mormon, ie existence of modern content, existence of some anachronistic problems like horses, etc, it may not be sufficient to explain ALL the criticisms, such as the existence of an ancient text at all. I say it ‘may not be’, because the theory is still in its infancy, and there may be faithful LDS more liberal than Ostler and Hardy but still more orthodox than the theory I’ll describe next. I’m not sure how far the Expansion Theory can be pushed in this way. Time will tell, as we see more developments.

Next, I will explore the theory I favor, which doesn’t assume any ancient text or ancient gold plates.

New Mormonism/Metaphorical/Sacramental/Emerging Paradigm View

I borrow this logic from Progressive Christian scholars. This is a more unorthodox theory in which the Book of Mormon could have no (or little) actual historie behind it and we should treat it purely in the heilsgeschichte tradition the way Christian scholars view the Bible. As scholars have come to a sharper view of how the Bible came to be and what is and what is not actually historical, educated Christian and Jewish believers have revised the logic of their faith. With 200 years to work on this, we now have a mature model of what that looks like.

From Project Gutenberg on “Bible Literalism”:

The style of Scriptural hermeneutics (interpretation of the Bible) within liberal theology is often characterized as non-propositional. This means that the Bible is not considered a collection of factual statements, but instead an anthology that documents the human authors’ beliefs and feelings about God at the time of its writing—within a historical or cultural context. Thus, liberal Christian theologians do not claim to discover truth propositions but rather create religious models and concepts that reflect the class, gender, social, and political contexts from which they emerge. Liberal Christianity looks upon the Bible as a collection of narratives that explain, epitomize, or symbolize the essence and significance of Christian understanding.

Liberal Christians will typically view subjects such as the Garden of Eden, Noah’s Flood, God’s ordering of the genocide of the Amalekites, and for some even the virgin birth and resurrection as metaphorical and not literal. Progressive Mormons using this theory of scripture would view characters such as Nephi and Alma and the existence of gold plates in a similar way: not to be taken literally but containing metaphorical spiritual value.

Christian scholar Marcus Borg in the book Heart of Christianity put some good context around how he sees the Bible and how the faith of liberal Christians shouldn’t be seen as inferior:

The Bible is seen as a human product. It’s man’s description of its relationship with God. It is not God’s witness to man, but man’s witness to God. This is not to deny the reality and power of God. But to acknowledge that scripture, even though we declare it to be sacred and treat it as such, is human in its origin and full of the possibility of human weakness and error.

Just as this view of the Bible does not deny the reality of God, it does not deny that the Bible is “inspired by God.” But it understands inspiration differently. In recent centuries, some Christians have understood it to mean “plenary inspiration”: that every word is inspired by God, and thus has the truth and authority of God standing behind it. For them, inspiration effectively means that the Bible is a divine product. Within the emerging paradigm, inspiration refers to the movement of the Spirit in the lives of the people who produced the Bible. The emphasis is not upon words inspired by God, but on people moved by their experience of the Spirit, namely, these ancient communities and the individuals who wrote for them.

By a sacramental approach, I mean seeing the Bible as sacrament. Indeed, this is one of its primary functions as sacred scripture. A sacrament is a finite, physical, visible mediator of the sacred, a means whereby the sacred becomes present to us. A sacrament is a vehicle or vessel of the sacred. In Christian language, a sacrament is an “outward and visible sign” that functions as “a means of grace.” Sacraments are “doors to the sacred” as well as bridges to the sacred. Something finite, something of this world, becomes a means whereby the sacred becomes present to us.

I believe we can view the Book of Mormon in the same way these Liberal Christians view the Bible.

I like Blake Ostler’s definition of scripture: ‘a synthesis of human creativity responding to divine persuasion.’ Now, I guess we can have a sliding scale of how much one sees the human element and how much one sees the divine element. A very fundamental thinking Mormon would say 100% divine. A very progressive thinking Mormon could say 100% human. Others would say some sort of split. I believe all could love and revere the Book of Mormon, faithfully serve side by side in the LDS church, and bear testimony of its truthfulness.

A big question on whether this view is tenable, is how we reconcile what Joseph said about the Book of Mormon. Joseph clearly said the Book of Mormon is an actual ancient record translated from actual gold plates after seeing and conversing with an actual angel.

I don’t have any perfect answers for this, but here are a couple points.

- Joseph might have misunderstood. By the church’s own admission, he didn’t understand what the Book of Abraham papyri was. My post reviewing Ann Taves’ naturalistic theory of the gold plates gets into the gold plates aspect of this. Maybe we misunderstand Joseph. He clearly used the word translate in a way we misunderstand him; what else could have we misunderstood?

- Christian scholars believe the early Christian fathers and other authors of the Bible acted in very similar ways (some might call it pious fraud) as Joseph Smith when it came to the creation of scripture, and they somehow find a way to make sense of that and maintain their faith in their religion. Progressive Jewish scholars do the same. Our “sins” are more recent and took place in an age with more documentation. Can Joseph be forgiven the same way the authors of the New Testament have been forgiven?

Another question is how possible will it be for literal/fundamentalist Mormons and progressive/metaphor Mormons to coexist in the same church and congregations. Liberal Judaism and Christianity have set a clear precedent that the model is valid. But, it seems a split in a church occurs to accommodate these views. It’s not as typical to find believers with this wide of range on the spectrum worshiping together in the same congregation. A challenge for Mormonism will be to see if an accommodation can be made without requiring a split in the church. In my view, so many of the positives of the church come from the community and organizational strength, I hope a split is not required. Watching how the Catholic church navigates this issue would be fruitful.

Conclusion

In a previous article, I showed how the Book of Mormon contains very specific ideas and phrases coming from 19th century discussion of the doctrine of the atonement of Jesus Christ. This article’s purpose was to explore whether that’s “OK”.

Whether the reader is prepared to accept my “New Mormonism” sacramental paradigm view or prefers the more traditional expansion view, I hope it can be accepted that the inclusion of modern elements in the Book of Mormon or historical inaccuracies (such as horses and chariots) does not automatically disqualify the Book of Mormon as scripture.

I love the Book of Mormon. The response LDS have to discovering the origination of the Book of Mormon might not be as “direct from God” as we might have thought shouldn’t be to discard it or downgrade it. We may not be as certain about things as we thought, but that’s OK.

My favorite moment researching this topic was finding this gem from Anthony Hutchinson’s article on Mormon Midrash. He talked about the feeling of loss he had discovering that scripture, whether it be the Bible or the Book of Mormon, most likely is not “God breathed”. This leads us right into larger theological questions.

The issues raised here ultimately feed into greater religious and existential questions of the uncertainty of all human knowledge, even that affirmed to be revealed from heaven. This issue is the one potentially most disturbing to Latter-day Saints who feel that somehow revelation resolves the problem of human uncertainty. I personally feel that we must be honest, must try to see the world as it is. If that means living with uncertainty, so be it. Such a view sees scripture and revelation less as cures to the disease of human uncertainty, than as stopgap medicines that help us endure a sometimes painful condition — not a disease, really, but simply the way we are. The stories we hold sacred, and tell to one another, rather than ridding us of doubt and giving us certainty, serve to help us raise our sensitivity and desire to serve, help us to find moral courage within ourselves, and make some sense, however fleeting, of our lives. When I first came to the conviction that Adam and Eve as described in Genesis were not historical figures, I suffered a sense of loss. When I realized that Joseph Smith’s opinions of Genesis were more reflective of his own understanding as a nineteenth-century American than of the ancient biblical tradition, I again experienced a certain disappointment. But as I came to see that these awarenesses gave me new understanding of these creation stories I loved so, and as I further understood the meaning and significance of the various scriptural authors’ contributions to the creation-story traditions outlined here, I saw that the stories still spoke deeply to me. Indeed, they in some ways gained new power because of their newly acquired clarity of meaning. Though my understanding of religious and scriptural authority changed, the stories’ power endured.

Many in the LDS church feel like they are going through faith crisis. Prior assumptions, based in fundamentalism and literal understanding of scripture and church history, are coming crashing down. This leads to uneasiness. It’s very difficult to move beyond this comfortable certainty that fundamentalist religion provides, and into the discomfort of uncertainty. There is a loss that we experience. But there is also growth and potential for deeper enrichment as we seek the truth about God and religion.

Ben Britton

Randall, nice job detailing the major positions on the the spectrum of belief on BOM historicity and offering validity to the alternatives from the traditional. It will be nice if some of this becomes more accepted in the church so that those of us outliers don’t have to spend our time trying to explain to others our position’s validity.

One thing you touched on is the most interesting questions in my mind. How much of the BOM is God vs. man? I think a contextual approach would be helpful, meaning if you can pair inspired-appearing content with clear purpose, you have a strong case for inspiration/revelation. I’m thinking for example of the money/measure system in Alma that apparently matches ancient near eastern weight/measurement systems. That is purportedly info that JS had no ability to have. OK, so that looks like revelation, but what’s the point? I don’t have one for that example, but if you had a compelling point you could make a stronger case for inspiration there. Anyhow, these are some ideas I’ve been kicking around and I thought they might interest you. I think they can be equally applied to modern expansion theory or a pure pseudepigraphal view. I’m curious if you’d add any other criteria by which you could strengthen or weaken the case for inspiration/revelation in a given passage.

Loren Evans

All of this is great apologetic gibberish trying to reason through some basic facts. The papyrus was stated by Joseph Smith to be the literal writings of Abraham as reported in the Mormon owned Nauvoo newspaper. Also Joseph Smith stated that ALL the indigenous peoples of the Americas were the literal descendants of the tribes of Israel. For 150 years those statements of Joseph were taught in earnest everywhere within the church. I can remember studying in Seminary both of these statements as documented in our book, The Restored Church, the literal writings of Abraham and ALL indigenous were descendants of the tribes of Israel. I can remember teaching on my mission these things, in particular, to the ‘Lamanites’ about their blessed heritage from the Lamanite seminary program.

Then the papyrus was found in Chicago and the deniers and apologists came up with all kinds of reasoning to say Joseph didn’t really mean what he said. Then the National Geographic Society did their ambitious genome testing of one million American indigenous peoples and discovered there was ZERO Israelite genes in any indigenous, that in reality the American indigenous came from the Mogollian peoples and the Pacific Island peoples came from southeast Asia. Suddenly the deniers and apologists are falling all over themselves coming up with reasonings of men to qualify what Joseph really meant from what he actually said.

Bottom line was Joseph was a shyster con man and now the Mormon church is doing everything possible for damage control except tell the truth. The very basic foundation was false that all the principles and doctrines was built on. As in the Book of Mormon, the keystone of the Mormon faith, is and has always been false and no amount of intellectual reasonings is going to change 150+ years of teachings as if they never existed.

Dee

The author is attempting to provide a new interpretation of the BOM and its history. Unfortunately there is simply too much on record that is authoritative in nature given by men like Joseph Smith that prevents this from happening and runs directly against ideas like Noah and the Ark being figurative.

All this will do is create cognitive dissonance. On the one hand, the ever amassing increase in modern evidence that clearly demonstrates a literalist interpretation simply isn’t viable, met with the hardline opposition of historic statements and even modern ones from LDS leaders. Elder Holland seemed pretty clear that there was an Adam and Eve in a Garden of Eden in his most recent conference address.

There is the common fair about Horses, Coinage, Steel, skeletal remains, lack of language evidence, DNA etc all being missing from the Americas and despite extensive archaeology across the Americas the findings simply have not been made (yet we’ve translated all 26 Myan languages).

But aside from these issues, the larger threat comes not from scriptural literalism, but from moral perception and the disconcerting realisation that the church hasn’t really given members full disclosure.

It is increasingly common knowledge that Joseph Smith had at least 34 wives. However try finding mention of this fact in the Joseph Smith the Prophet manual. It becomes apparent that it simply has not been taught in the church in decades that Joseph Smith was polygamous, as such, upon hearing this many members feel it is a lie, an anti mormon accusation. However church history confirms it is a fact. This then leads to some members wondering why they weren’t told. There is the stock answer about it being relevant to your salvation, but such remarks carry an air of communist censorship about them, the authorities decided not to disclose all of the facts to your mind. Such a nanny type of approach does come across as somewhat orwellian, and doesn’t sit well with the American mindset. Oddly, the realisation that you can actually find out more about LDS early history by reading the CESletter than by attending sunday school IS greatly concerning. What were portrayed as anti lies turn out to be more accurate statements than we find in official manuals. Again, Cog Dis and the creation of distrust in LDS sources.

The moral problems arise when we see JS marrying Helen Mar Kimball. Brian Hales has gone to great lengths to make this marriage of a 37 year old man to a 14 year old girl a non sexual relationship. But Hales is basing his opinion on speculation. He has no evidence to support that view, instead he relies on the absence of evidence of directly stated sexual activity between the two – upon which basis there would be no evidence i had sex with my wife for the first few years until kids later came along.

But sex isn’t the only issue (despite it being the sole grounds for permission of polygamy in both the BOM and the D&C – to raise seed). The very idea that a 37 year old highly respected leader of the community, the man who speaks with God, could give a 14 year old just 24 hours to make a decision upon which her eternal salvation or damnation dependent (saved if she said yes, damned if no) is astonishing. How does such a coercive act sit with the idea of free agency? Is it morally right that Emma Smith had no knowledge of this? If Joseph can approach any woman he likes without Emma knowing, then isn’t he really just like a single guy and can in effect ‘date’ or chat up women. And, when these women are married, isn’t it adultery to meet with them without their husbands knowledge to attempt to solicit them into a celestial marriage? I know if a guy was secretly meeting my wife and they were discussing being married behind my back i’d class that as adultery in the heart even if no sexual activity had taken place. Today, LDS youth can’t even date until they are 16, yet Smith married a 14 year old. Smith claims God commanded him to do this, which creates the challenging idea that God is ok with Child brides. If so, why can’t kids marry today at 16? Has Gods standard changed?

So modern LDS members begin to discover that not only is a literalist interpretation of scripture infeasible, but that such a view requires them to discount authoritative statements made by foundational LDS leaders, and realise that it is the church itself that isn’t giving them the true and full account of LDS history, and that the true history whips up a whole host of moral issues that people simply are not comfortable with (ala the celestial swinging that Polyandry is).

Some members deal with this head on and leave the church. Others try to ignore it and bury it in the back of their minds. Some think the whole thing is ok, child brides and all. How each person reacts is down to their own moral compass, but my suspicion is, those with a modern sense of morality will increasingly leave, and those who are ok with some of the history will stay. As a result, the LDS church will increasingly struggle to look distinguishable from the fundamentalist mormon groups in terms of ideology. Whilst it may no longer practice polygamy and polyandry at the moment, it will recognise it is an eternal doctrine – which means the gap between Warren Jeffs and LDS Mormonism isn’t ideological or doctrinal, it is purely one of authority.

My suspicion is, this isn’t a message you can sell to the western world and gain converts.

Ben Britton

I believe Randall is acknowledging the faults/untruths of the historical record. He suggests that man/JS is creatively responsible for an undefined (at this point) portion of his revelations (BoM, BoA, etc.).

He seems to, like Dan Vogel, believes JS is sincere despite his revelations often appearing to be a product of the culture and time period. Unlike Vogel, it appears that he still allows for inspiration amidst the manmade mess.

I tend to agree with this stance due to some of the more mysterious features of the text coupled with the connection to God I’ve personally experienced through them. One of your questions is how do you reconcile this approach to the JS claims about his texts. In the end, you don’t. You end up having to decide whether or not he was sincere, but either way he was wrong to some degree or other.

sotteson

I have seen Vogel say it’s not up to him to say whether Joseph was inspired or not, since that’s not a question for historians. Even if the Book of Mormon is a complete fabrication from Joseph Smith, it can still contain stories and principles that inspire others to do good. I would say the same is true for other books people consider to be inspired, such as the Koran or Dianetics. I don’t believe any of them were literal revelations from God, but I recognize they have an ability to help people in very real ways.

Dave McGrath

Oh thank you for writing this! You’ve not only explained away Mormonism, the ‘Prophet’ Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon – but you’ve completely deconstructed Christianity. Let’s see if I got this right: The bible is a fiction and similarly the Book of Mormon is a fiction. Therefore, if you are gullible enough to believe the Bible, then you shouldn’t have any problem believing the Book of Mormon. Did I get it right?

Tom Marsh

Thank you so much. You have inadvertently provided such a wealth and insight into the mind of the shifting and leanings and blindspots of the apologist that believes himself to be so wise as to craft yet another defense of the indefensible. The vacancies in the jumps of logic are not only unacceptable, but would also be completely unacceptable to you if something similar had been written in defense of (for example) ‘The Sealed Portion’. I don’t, however, wish to discourage you and I won’t be taking anything of a discussion here. Your blog is perfect and has been such a wonderful display for those who are realizing the doctrines and history we have been raised with is crumbling beneath our feet. One just has to come here and realize …’No, I don’t want to be twisting myself around the necessary nuances of this false belief system. Time for me to go.’ Sincere and kind regards.

Shurr

‘ In a previous article, I showed how the Book of Mormon contains very specific ideas and phrases coming from 19th century discussion of the doctrine of the atonement of Jesus Christ. This article’s purpose was to explore whether that’s “OK”. ‘

You need to take a look at Skousen’s March 2015 BYU presentation. He addresses Campbell’s list directly and tangentially mentions phrases that have been thought to be late 18th-, early 19th-century. Your phrase list contains language that doesn’t originate in the 18th and 19th centuries. It derives from earlier centuries. This means that what you have presented in your previous post is inconclusive evidence. You probably haven’t consulted the database Skousen mentions that must be used in addition to Google. As a result of the time depth of these phrases, one cannot say with certainty that these phrases were derived from JS’s time. Also, Skousen addresses many BoM themes that could just as well be thought of as Reformation concerns. Again, inconclusive. This thematic stuff will never be as solid as the harder English linguistic evidence, which is subconsciously produced by speakers and writers to a high degree, as opposed to content. Next year Skousen will publish as part of the critical text project material showing that phrases such as ‘infinite atonement’ are old.

churchistrue

Interesting. I look forward to the ‘infinite atonement’ research. I don’t have access to Skousen’s same tools for research, and I’m just a hobbyist. I’ll never match the level of research he and his team or other scholars can do. I see myself as collating existing research and ideas. I’ve been fascinated by the 16th century translation committee theory for quite a while. I look forward to advancements in the research and theory. I don’t find it compelling yet, but I do find it interesting. Thanks for your comment.

churchistrue

Interesting. I look forward to the “infinite atonement” research. I don’t have access to Skousen’s same tools for research, and I’m just a hobbyist. I’ll never match the level of research he and his team or other scholars can do. I see myself as collating existing research and ideas. I’ve been fascinated by the 16th century translation committee theory for quite a while. I look forward to advancements in the research and theory. I don’t find it compelling yet, but I do find it interesting. Thanks for your comment.

Shurr

This 1654 book is publicly available and has ‘infinite atonement’: books.google.com/books?id=_AE8AQAAMAAJ.

churchistrue

I would like to hear a detailed explanation of Skousen’s theory. I have heard bits and pieces but not sure how it all fits together. I don’t understand how it would affect, for example, this modern expansion concept. Whether the ‘modern expansion’ occurred in the 16th/17th century or in the 19th century, there is still a modern expansion, right?

Scott Mitchell

For some reason you didn’t post Jack Lyon’s original comment to you, but that which you did post from him, I agree with. Your two articles completely ignore the research from Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack which establish that the ‘translation’ process was TIGHTLY controlled, word for word, with Joseph Smith having no authorial or editorial input at all. Joseph merely read what was written in English in the instrument and dictated what he was reading, but it was so foreign to him, he later started trying to change everything in it he thought was wrong. He thought the Hebraisms were bad grammar or too redundant, he thought the English grammar was bad and needed correcting, and he thought some of actual doctrine had to be a mistake. This was all because he didn’t recognize Early Modern English grammar or expressions, and he was unfamiliar with Hebrew expressions and grammar as well. That is the landmark finding of Skousen and Carmack–the BoM was translated into an obsolete Early Modern English in use during the period from 1470-1740 AD, with which Joseph had no familiarity, but which he could still read Other studies which support this conclusion have focused on the counterintuitive fact that Joseph Smith never seemed to as familiar with the BoM text as other early converts were. He didn’t remember what was written in the BoM, he didn’t quote from it much, and he affirmatively forgot some of its most high-profile teachings. His major sermons were, after 1830, not based on BoM text, but on biblical texts, because he flat-out didn’t know that much about it. This research shows that no one in Joseph’s time could have written or revised the BoM, because it is so full of completely obsolete Early Modern English, no was left alive in 1830 who possessed the requisite knowledge of 15th and 16th century grammar and expressions to compose its original, pre-edit form.

Right here, I will add something that others won’t say, either because they don’t dare, or because they don’t agree. But when Joseph Smith appears to have faked a translation, it’s because he did fake the Book of Abraham and his ‘translation’ of the Bible. The evidence is overwhelming that those are fakes, and Joseph Smith was terrible at covering up when he was truly faking something. But the same evidence cuts the opposite way with the BoM. There is way too much in the BoM that Joseph COULDN’T have faked, because he was simply too uneducated to fake it. The latest research is showing that no one on earth could have faked the BoM, because no one alive in 1830 had the knowledge to do it. And that’s, ironically, one of the biggest testimonies of the Book of Mormon’s authenticity: when Joseph faked something, it was immediately apparent to any thoughtful person that he had done so. But Joseph not only couldn’t fake the BoM, no one could. And unless you’re conversant not only with Skousen and Carmack’s work, but Welch’s, Stubbs’, Aston’s, and Magleby-Hauck-Anderson-Grover-Sorenson, et al, you’re going to be repeating theories that lost credibility decades ago.

churchistrue

Thanks for engaging the article and your comments. I think Skousen-Carmack succeed somewhat in showing the tight translation. But I call it tight dictation. I would best explain it by saying he is dictating, at least at times, a text he is either seeing in his head, or has memorized, or reading off paper. Skousen-Carmack’s work proving the EModE grammar and expressions tie it to a 17c translation, I don’t buy. I think most likely the counter to that is that over time, research will come for that their is a better explanation for that, such as a 19c author mimicking EModE. Or maybe even the existence of rural grammar or dialect that was preserving EModE. I admit Skousen-Carmack’s work on proving 17c translation would blow my theory and most all other current theories out of the water. I guess we’ll see what happens. As for the work by the old FARMS and others showing Mesoamerican bullseyes, etc. I don’t find most of that very compelling.

Scott Mitchell

I might add that Skousen and Carmack affect the ‘modern expansion’ theory in this way: They show that the BoM language PRE-DATES the language you’re quoting as evidence the BoM borrowed from earlier theological discourse. In other words, the expansion theory only makes sense if you can argue that Joseph Smith was aware of certain theological writings and discussions that had preceded him (a dubious proposition to begin with, in my opinion, since it ignores Smith’s well-documented profound ignorance of even basic biblical knowledge; he never even realized that Elijah and Elias were the same person, much less what biblical scholars were writing about while he was plowing fields) and enlarged on those themes when we wrote the BoM. But once it’s shown conclusively that not only was Joseph Smith unaware of he was using grammar and expressions that had long since disappeared, but no one else alive recognized the linguistic antiquity either, the expansion theory doesn’t work. A person can’t expand on something they’re completely unfamiliar with.

So, you’re not interpreting correctly what you’re seeing. The phrases you think are borrowed from others are phrases that survived from the Early Modern English era, and are still in use in Joseph’s time. But most of the phrases from the EME era DIDN’T survive for Joseph (or anyone else) to borrow, but they still show up in the BoM, and until the last few years, we didn’t know of their prior existence.

That’s where Skousen’s ‘translation committee’ idea becomes relevant. He originally postulated that for some reason, people living in the 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th centuries labored away at translating the reformed Egyptian on the plates into an English which Joseph couldn’t speak or write, but could easily read, from a bygone linguistic era no longer in use. If this is true, it means that this committee was using translation decisions being made by others (Coverdale, Tyndale, many other writers and speakers from that era, and the KJV team) and adapting them to slowly render the text on the plates into a language Joseph would later be able to read. So, was borrowing going on? Doctrinally, no. But linguistically, yes, of course. That’s the only way translation is done. You figure out the closest equivalent in the new language from the language you’re trying to translate, and you use that expression. Some simple concepts translate smoothly, but most just don’t. When you’re on that committee, and you read or hear someone coin the phrase ‘infinite atonement,’ for example, you think to yourself, ‘Wow, that’s sounds like a handy way to express ‘a surrendering of His own life on one occasion only, which self-sacrificing act has effect forever for all mankind, and applies equally to everybody, and provides an escape from the consequences of sins committed during mortality.’ I think I’ll adopt that term for the Book of Mormon text.’

If you wish to discuss this issue more, or any other issue, such as BoM textual clues as to who would have comprised the ‘committee,’ I can be reached through the now-online LAMP site at osaywhatistruth.org , though that site is still under construction and hasn’t launched publicly yet, or at 2020scottmitchell7@gmail.com.

Jack Lyon

‘ I don’t have access to Skousen’s same tools for research’

No, but you do have access to his thinking about all of this. Please see here for the details (and scroll down to the links):

http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/books/volume-4-of-the-critical-text-of-the-book-of-mormon-analysis-of-textual-variants-of-the-book-of-mormon/

All of this theorizing is interesting, but until you’ve actually *read* Skousen’s work, you won’t really understand what’s going on. And what *is* going on is absolutely fascinating.

More here:

http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/author/royals/

And here:

http://mi.byu.edu/tag/critical-text-project/

By the way, the plural of ‘Rabbi’ is ‘Rabbis,’ not ‘Rabbi’s.’

Cristy

I’m new to your site and I would like to say I find your posts fascinating. I’m glad you’ve made peace with all of the craziness that can come from finding out the historical accuracies of the church. I also wanted to say, after reading just 2 posts, my only hangup with your argument of ‘let’s just all continue to serve together and there is good in the church to be had and it’s OK the real story isn’t factual or historical as we all once believed’ is this: we pay, literally in money, to buy our salvation through this medium we believe God has restored on the earth through JS. JS made real, definitive statements about how things played out. Those statements have been preached and preached for decades, dictating to us how we earn our salvation. And now we are being asked to redefine all those statements (on our own, mind you, because the church is STILL pushing the old narratives. No expansion theory is being heralded from the pulpit that I’ve heard) and do all kinds of mental gymnastics so we can, what? Continue to pay 10% of our earnings and have church callings that pull us away from our family many, many hours out of the week so that we can appease God who, when He said we MUST do these things to get back to heaven, was being literal and straightforward THEN but at NO OTHER time, apparently, was He being literal or as straightforward? This doesn’t even sound right, much less feel right. I get that some people need the church. I enjoy the social part of church also. And if the church wants to adopt the expansion theory and all of the other more progressive, nuanced views of this religion, I would be happy to vocally support them. But if they do then they MUST stop dictating that this church is the ONLY way to salvation. Salvation through temple endowments must stop being taught as an absolute, heavenly mandated requirement. They can’t have it both ways.